An unnoticed provision in the Senate’s latest reconciliation bill goes beyond just selling public land – it aims to strip local communities of their control. This provision prohibits states and counties from regulating “AI Systems” for a full ten years, paving the way for secretive development extending far beyond housing. From data centers to deed-restricted zones, this bill reshapes who holds influence over the future of American land.

The extensive bill also impacts the Endangered Species Act (ESA)—specifically its private right of action, a legal tool that enables activist nonprofits to halt land use activities.

As the Senate deliberates on a proposal to sell off 3.3 million acres of federal land, this obscure clause is driving a significant shift in who controls America’s landscapes.

However, legal battles are only part of the story. The other part is what occurs post-land sale.

The larger concern that is not being addressed here is the private right of action that restricts state lands held in trust in ALL 50 states by extreme environmental law firms like the Centers for Biological Diversity. CBD funds numerous far-left NGOs through lawsuits…

— Breeauna Sagdal (@Breeauna9) June 19, 2025

A Dual-Directional Lockdown

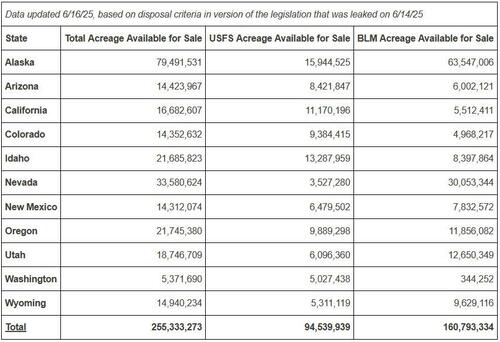

The Senate Reconciliation Bill (H.R.1) proposes to sell 2.2 to 3.3 million acres of BLM and Forest Service land—around 0.5% to 0.75% of Western federal holdings. However, hidden in the details is something more concerning: the bill renders over 250 million acres eligible for private nomination, with no public input, no affordability requirements, and no obligation to disclose the purchaser.

In essence, a technocrat’s dream concerning the infrastructure needed to support AI empires…

Even more alarming is Section 43201(C) of the bill, which critics argue could restrict state or local governments from regulating land use due to its overly broad language on “AI systems.”

Skeptics, including Beef Initiative policy analyst Breeauna Sagdal, point out this section’s vague and expansive language could inadvertently override local regulations beyond AI, potentially impacting land use if AI tools are involved.

Local regulations that could be superseded include laws addressing bias algorithms in housing development, or in criminal justice such as the Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS) system, or predictive policing systems—banned by many municipalities nationwide.

Others argue that “A.I. Systems” could be interpreted by relevant administrative agencies (who serve at the President’s will) to mean data centers or physical locations. In this scenario, local zoning would be affected due to the federal government’s preemption right for a decade.

The Big Beautiful Bill contains a provision prohibiting state & local governments from regulating AI.

It’s more concerning than you think.

It would facilitate corporations obtaining zoning variances, enabling massive AI data centers to be constructed near residential areas. pic.twitter.com/w7pLJLq4nZ

— Thomas Massie (@RepThomasMassie) June 5, 2025

Put simply: the bill not only sells the land. It precludes local authority, creating a significant risk contingent on the White House administration.

The Litigious Economy

On the flip side of the legal spectrum are state lands held in trust—parcels designated to states to generate revenue for public schools and offset taxes. Many of these parcels remain undeveloped not due to market conditions but because of Endangered Species Act (ESA) lawsuits.

Under Section 11(g) of the ESA, groups like the Centers for Biological Diversity (CBD) have been incentivized to sue state and federal agencies, earning millions while coercing policy changes.

A single lawsuit has the power to halt any project—grazing, wildfire prevention, or even school infrastructure.

CBD boasts a 93% success rate in court and finances activities partly through attorney fees recovered from these victories. Their legal strategy has shaped national land use policy and generated millions in the process.

Meanwhile, state lands held in trust remain unmanaged. Fires proliferate. Revenues disappear. And the public is excluded from decision-making.

This Isn’t Just a Land Sale. It’s a Lockout.

While the Senate bill is pitched as a housing remedy, the majority of BLM and Forest Service lands are situated far from existing infrastructure. According to Headwaters Economics, only a small portion—estimated at under 2%—is close to communities where housing demand exists. Additionally, the bill lacks language mandating affordability, density, or public-oriented outcomes, leaving room for upscale or speculative development.

Coupled with Section 43201’s 10-year restriction on state AI regulation, potentially affecting local land use regulations, and various federal regulations concerning land acquisition and eminent domain use, a different narrative emerges.

This isn’t about residences.

It’s about centers.

Data centers.

Energy centers.

Logistics corridors.

The foundation of future smart cities, surreptitiously grafted onto formerly public land.

Legal Overhaul? Don’t Anticipate It.

In early 2025, the Trump administration proposed narrowing the ESA’s definition of “harm” to exclude habitat destruction—an effort to reduce litigation hurdles. However, the fundamental legal weapon—the private right of action—remains unchanged. Only Congress has the authority to revoke it.

Until then, public lands remain susceptible to two potential outcomes:

Tied up in litigation.

Or auctioned off devoid of local oversight:

Either way, private property rights are jeopardized, despite assertions online that this addresses the 30×30 goals of Agenda 2030.

Glenn, as a rancher, I have some serious concerns about this section AND section 43201c—mainly for how the unelected bureaucrats will interpret this in the future.

1. The private right of action in the Endangered Species Act that has allowed radical far-left activists to lock…

— Breeauna Sagdal (@Breeauna9) June 20, 2025

Conclusion: A Trend, Not a Policy

When land is paralyzed by lawsuits or wrested from local control post-sale, what remains is neither safeguarding nor advancement. It’s a transfer—of authority, of access, of rights.

The ESA’s citizen suit provision, once a tool for public accountability, now serves as a barrier to state and rural land use. The Senate’s land sale bill, marketed as a housing solution, conceals within it the legal framework of exclusion: top-down sales, bottom-up litigation, and the complete elimination of local influence.

It’s not just about the land.

It’s about who has the power to steer the ship of control.

A precarious unknown, contingent on future election outcomes.

Loading…