Authored by Michael Lebowitz via RealInvestmentAdvice.com,

In the quest to combat inflation and reach the 2% target, the Federal Reserve is hesitant to implement interest rate cuts. Their stance is based on the belief that high interest rates lead to lower inflation. While many investors trust the Fed’s wisdom and logical theories, could they be mistaken? Is it possible that lowering interest rates is actually the solution to reducing inflation?

As economist John Maynard Keynes once remarked:

The difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from old ones

Science, including the field of economics, revolves around discovering knowledge. Throughout this process, established truths may be discarded as falsehoods, while new truths emerge as accepted facts, albeit temporarily in most cases.

Consider the following “facts” that were once widely held as truths:

-

The Earth is flat and the center of the universe.

-

Heavy objects fall faster than lighter ones.

-

Housing prices always increase.

-

Trickle-down economics works.

In the spirit of Keynes’s advice to “escape” from conventional Fed ideas that are perceived as truths, let’s explore a counterintuitive theory regarding rates and inflation, inspired by a white paper authored by the St. Louis Fed nearly a decade ago.

Milton Friedman

To grasp the prevailing inflation logic embraced by the Fed and most economists, it is essential to delve into the work of economist Milton Friedman. Perhaps best known for his assertion:

“inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.”

This theory implies that price fluctuations are tied to the money supply. In the late 1970s, central bankers put Friedman’s theory into practice to combat rampant inflation by managing the money supply.

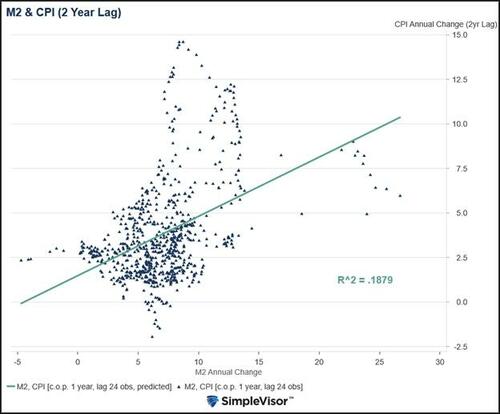

The scatter plot below illustrates the annual changes in CPI and the money supply (M2) since 1970. CPI is lagged by two years for the most robust statistical relationship, although its relatively weak correlation is reflected in the R-squared value. The weak relationship stems from monetary velocity, a key driver of inflation, influencing the results.

Recognizing the limited link between the money supply and inflation, many central banks shifted their focus from targeting the money supply to targeting interest rates.

Although the instrument used to influence inflation has evolved, the impact remains similar.

All money is created through lending. Hence, higher interest rates discourage borrowing, leading to slower money supply growth. Conversely, lower rates incentivize borrowing, fostering faster money supply growth.

Neo-Fisherism

Despite the common practice of using the money supply or interest rates to manage inflation, this approach has proven ineffective, especially in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

Following the financial crisis, central banks, including the Fed, struggled to achieve their target inflation rates despite maintaining near-zero interest rates, and in some instances, negative rates, alongside regular quantitative easing (QE) measures.

In 2016, Stephen Williamson of the St. Louis Fed penned an article titled Neo-Fisherism: A Radical Idea, or the Most Obvious Solution to the Low-Inflation Problem?

He highlighted the central banks’ predicament:

Now, in 2016, these central banks are typically experiencing inflation below their targets, and they seem powerless to correct the problem. Further unconventional monetary policy actions do not seem to help.

The article delves into a potential flaw in zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) and QE— the Fed’s primary tools for stimulating inflation.

Irving Fisher And The Neo-Fisherites

Williamson’s paper builds on economist Irving Fisher’s insights into how interest rates, the money supply, and inflation expectations shape economic outlooks.

In the mid-2010s, Williamson and other economists, dubbed Neo-Fisherites, presented a simple argument to central banks. Economist and journalist Noah Smith summarized their theory:

What if quantitative easing had the opposite effect of what was intended? This is the contention of a group of macroeconomists, known as the “Neo-Fisherites,” named after the renowned monetary economist Irving Fisher. These economists question whether quantitative easing actually reduced inflation, contrary to fears, and go further to suggest that low interest rates, typically viewed as inflationary, might be deflationary!

Neo-Fisherite Theory

The Neo-Fisherite theory posits a positive correlation between interest rates and inflation, as opposed to the conventional negative correlation, based on the Fisher formula:

R = r + π

R (Nominal interest rates) = r (real interest rates) + π (expected inflation)

The following excerpt is from Stephen Williamson’s article.

If the central bank raises its nominal interest rate target by 1 percent and sustains this indefinitely, what occurs? While central bank policy typically impacts real economic activity in the short term, these effects diminish over time. Therefore, in the long run, the nominal interest rate increase solely results in a corresponding inflation rate rise. In essence, the nominal interest rate’s influence on inflation is manifested through the Fisher effect; thus, a 1 percent rise in the nominal interest rate should correspond to a 1 percent inflation rate increase in the long run.

The crux of the argument is that interest rate adjustments have immediate effects on the economy and inflation, but in the long term, inflation expectations play a more significant role in shaping inflation.

Williamson’s graph demonstrates that while an interest rate hike initially raises the real rate, it gradually declines as expected inflation rises over time.

Have Rates Been Too High For Too Long?

The absence of specific dates or timeframes on the X-axis of the graph poses a perplexing question:

over what timeframe do inflation expectations exert a greater influence than the diminishing benefits from rate adjustments?

Answering this question proves challenging due to various variables affecting inflation, many of which are complex to quantify.

Could inflation expectations be influenced by monetary velocity, resulting in persistent inflation levels due to the Fed’s prolonged high-interest rate policy?

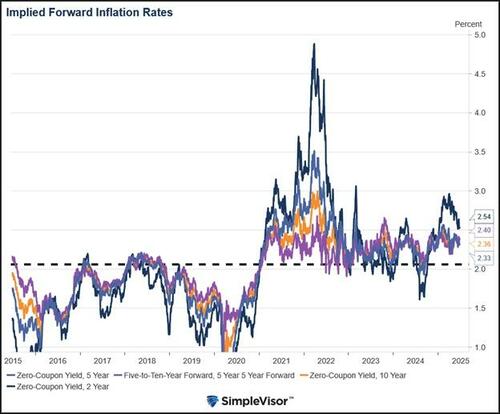

The graph below depicts a notable shift in inflation expectations before and after the onset of inflation in 2021.

Summary

Williamson poses a compelling query:

If the central bank aims to reduce inflation, should it lower the nominal interest rate target?

While inflation expectations likely contribute to the elevated inflation levels, high interest rates dampen economic activity, curbing demand and ultimately inflation. The housing market serves as a pertinent example.

Should the Fed heed Williamson’s suggestion and reduce rates, a temporary inflation surge might ensue due to the marginal economic benefits of lower rates. However, in the long term, inflation expectations could diminish, leading to lower inflation levels.

We urge Powell to weigh both sides of the argument and refrain from succumbing to political pressures, prioritizing long-term inflation reduction.

Loading…