Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

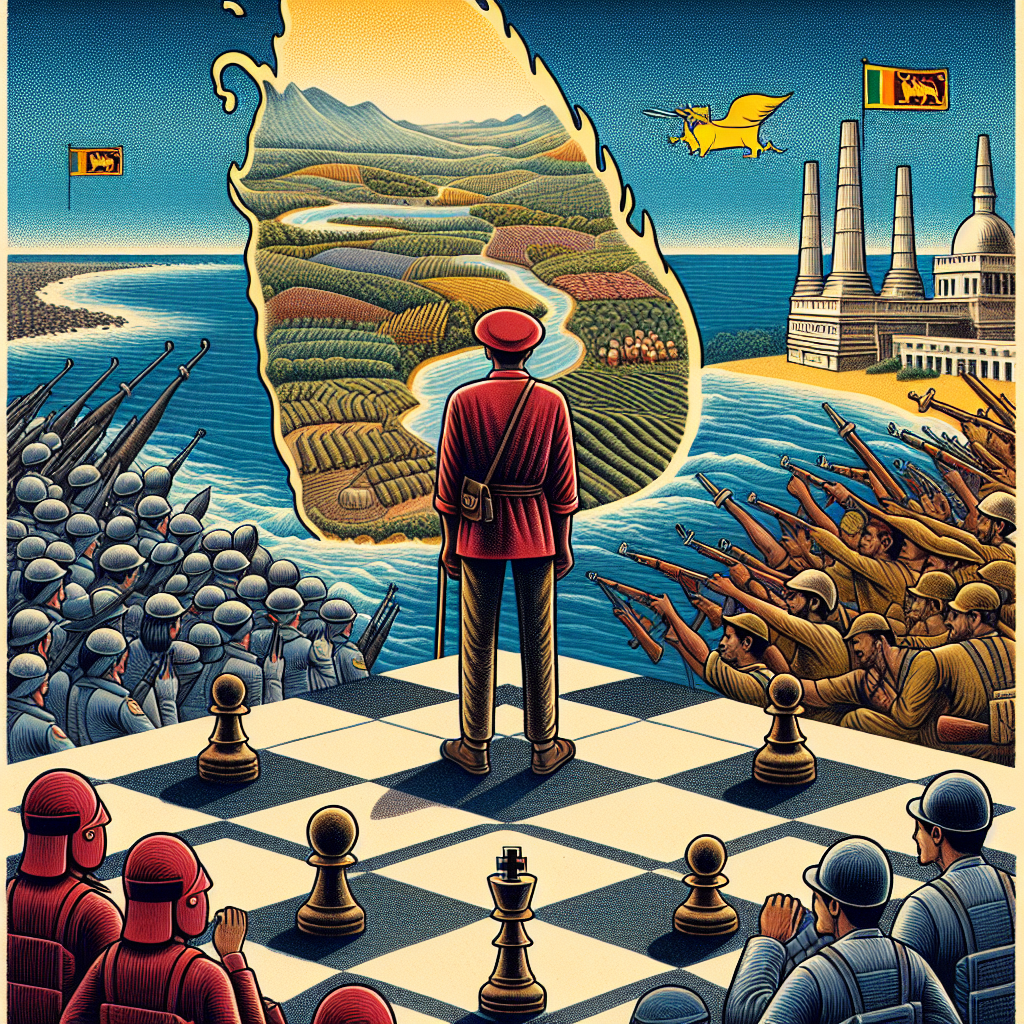

“A fresh start.” That is how the leftist outsider candidate, Anura Kumara Dissanayake, touted his against-the-odds victory in Sri Lanka’s presidential election over the weekend. The island nation certainly needs a new beginning. For the Sri Lankan people, the past few years are best forgotten.

In 2022, the government defaulted on its debt for the first time, as its economy battled the impacts of the pandemic and high commodity prices. Fuel, food and medicine supplies were running short, inflation was soaring, and angry protesters ransacked the then-president Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s palace, forcing him into exile. The economy stabilised under his successor Ranil Wickremesinghe, but only alongside unpopular spending cuts and tax hikes, conditions of a $2.9bn IMF bailout he negotiated in 2023.

In Saturday’s election, Sri Lankans voted to take a chance on the inexperienced neo-Marxist, Dissanayake. They have grown frustrated with the chaos, corruption and economic mismanagement that they associate with establishment politicians. Dissanayake swept aside incumbent Wickremesinghe, also a former six-time prime minister, and main opposition leader Sajith Premadasa, the son of a former president.

The question is whether Dissanayake can now deliver for the Sri Lankan people. His manifesto included ambitious proposals to end graft, slash poverty and drive economic growth. It also promised to tweak the IMF bailout to make it “more palatable”.

All of that is easier said than done. His National People’s Power alliance has little administrative experience. The president has already struggled to pull together a cabinet, and will need to rally support from a parliament filled with establishment parties, where the NPP currently hold just three out of 225 seats. On Tuesday, he called a snap election, which will take place in November, in a bid to seek a stronger mandate. A solid performance for his coalition is key, or his task would become even harder.

Reworking the IMF deal is also central to unlocking Dissanayake’s broader economic agenda. Sri Lanka’s foreign reserves have improved, but it still has only a few months of cover for its imports. Reopening discussions with the multilateral lender risks delaying crucial funding, and upsetting a linked effort to restructure $12.5bn of defaulted bonds with creditors. But to shift a greater burden of austerity on to the wealthy, and to fund plans for tax reliefs and investments, the new president needs to convince the IMF, external creditors and domestic politicians to flex the country’s existing fiscal plan.

Sensibly, he has said that he would preserve the IMF deal, but look for wriggle room where possible. He has distanced his party from its gory past, and has toned down its hard-left stance. That should continue in office. The new Sri Lankan administration needs to gain the confidence of lenders and investors, and prove it has a viable long-term plan for debt sustainability. That should include efforts to broaden Sri Lanka’s tax base and improve revenue collection.

But a lot depends on the leeway the IMF is willing to offer. It may be possible to tweak austerity plans to lower the burden on the poorest households within the IMF’s current spending parameters, but voters will be looking for more. As the fund is finding out with its programmes elsewhere, long-term sustainability in public finances requires both painful economic reforms and political stability. Allowing the new Sri Lankan government time to put forward a new economic plan and being open to credible amendments make sense.

As he was sworn in on Monday, Dissanayake sought to manage expectations. “I am no conjuror or magician,” he said. Indeed, Sri Lanka may have a fresh face in power, but no single individual can turn the nation’s fortunes around. For that, parliamentarians, the IMF and creditors will have to work in concert.