Authored by Bradley Hope and Clara Preve via whalehunting.projectbrazen.com,

Alex Saab may control $60 billion in Bitcoin for the Maduro regime. As Trump’s naval blockade tightens, the real battle is being fought on the blockchain.

Nicolás Maduro is in U.S. custody. In the early hours of Saturday morning, Delta Force operators dragged the Venezuelan president and his wife from their bedroom in Caracas and flew them to the USS Iwo Jima, now steaming toward New York where Maduro will face drug trafficking and weapons charges in federal court.

But as Washington celebrates the most dramatic U.S. military operation in Latin America since the 1989 Panama invasion, a more urgent question is emerging in intelligence circles: Where is the money?

For years, Maduro and his inner circle systematically looted Venezuela—billions in oil revenue, gold reserves, and state assets—and, according to sources with direct knowledge of the operation, converted much of it into cryptocurrency.

The man who allegedly orchestrated that conversion, who built the shadow financial architecture that kept the regime alive under crushing sanctions, is not on that ship.

His name is Alex Saab.

And he may be the only person on Earth who knows how to access what sources estimate could be as much as $60 billion in Bitcoin—a figure that, if verified, would make the Maduro regime’s hidden fortune one of the largest cryptocurrency holdings on the planet, rivaling MicroStrategy and potentially exceeding El Salvador’s entire national reserve.

The claim comes from HUMINT sources and has not been confirmed through blockchain analysis, but the underlying math is provocative.

Venezuela exported 73.2 tons of gold in 2018 alone — roughly $2.7 billion at the time. If even a fraction of that was converted to Bitcoin when prices hovered between $3,000 and $10,000, and held through the 2021 peak of $69,000, the returns would be staggering.

Sources familiar with the operation describe a systematic effort to convert gold proceeds into cryptocurrency through Turkish and Emirati intermediaries, then move the assets through mixers and cold wallets beyond the reach of Western enforcement.

The keys to those wallets, sources say, are held by a small circle of trusted operatives—with Saab at the center.

What Washington didn’t know—and what court documents would later reveal—was that Saab had been a DEA informant since 2016, even as he built Maduro’s shadow financial empire.

Now, with Maduro captured, the question becomes: Will Saab cooperate again? Or will he disappear with the keys to Venezuela’s stolen fortune?

Alex Saab embraces Nicolas Maduro upon his return to Caracas, December 2023. With Maduro now in U.S. custody, Saab may hold the keys to Venezuela’s hidden crypto fortune.

In the official Venezuelan narrative, Alex Nain Saab Morán is a patriot, a diplomat, a martyr of U.S. imperial overreach. In Washington, he is the opposite: a professional sanctions-evader who built a labyrinth of offshore companies that enriched Nicolás Maduro’s inner circle while Venezuela collapsed.

Now he may be something else entirely: among the most valuable people on earth.

But Saab is not the only person who knows where the money went. Whale Hunting has learned that a key figure in the gold-to-crypto pipeline—a man who allegedly served as a physical courier, flying gold bars from Venezuela to Turkey and Dubai—was sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury in 2019 but has never been publicly charged.

His name is David Nicolas Rubio Gonzalez. He is the son of Álvaro Pulido, Saab’s longtime business partner. And his story may be the key to understanding what happened to Venezuela’s stolen fortune.

The Courier

On September 17, 2019, the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control added David Nicolas Rubio Gonzalez to its sanctions list. The designation identified him as controlling at least three companies: Corporacion ACS Trading S.A.S. in Colombia, Dimaco Technology, S.A. in Panama, and Global de Textiles Andino S.A.S. in Colombia.

His father, Álvaro Pulido, had been indicted by the U.S. Department of Justice two months earlier, charged alongside Alex Saab with laundering more than $350 million from fraudulent Venezuelan state contracts. But David was not charged. He was sanctioned—his assets frozen, his ability to do business with Americans severed—but he faced no criminal prosecution.

Why?

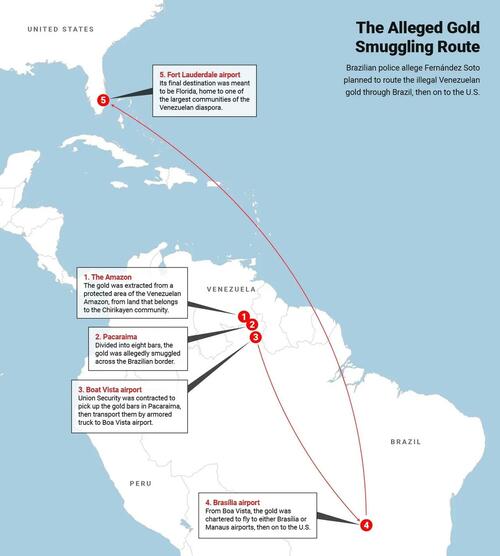

According to sources with direct knowledge of the operation, David Rubio Gonzalez was not just a businessman. He was a courier. These sources describe a network that physically moved gold along a route from the Dominican Republic through Venezuela to Turkey and Dubai. Each trip, they say, netted the courier $1 million for his services.

The gold originated in the Arco Minero del Orinoco, a vast mining zone in eastern Venezuela. It was purchased by the state-owned mining company Minerven, processed by CVG Minerven—whose president maintained close ties to Saab—and transported abroad by private aircraft or Turkish Airlines commercial flights. But moving gold at scale requires trusted hands. Someone has to physically carry it, clear customs, deliver it to the refineries and brokers who convert it to cash.

David, sources say, was one of those hands.

Venezuelan gold moved through Turkey, the UAE, and Iran before conversion to cryptocurrency. Couriers like David Rubio Gonzalez allegedly earned $1 million per trip.

The question that haunts investigators is simple: If David was important enough to sanction, why wasn’t he important enough to indict? His father faced eight counts of money laundering. David faced none.

There are only a few explanations. He could be cooperating with U.S. authorities—providing information in exchange for immunity or a reduced role in any future prosecution. He could be under sealed indictment, his charges hidden from public view until the moment of arrest. Or he could have simply slipped through the cracks, a secondary player deemed less important than the principals.

But if our sources are correct about his role as a courier—a man who physically handled the gold that became the regime’s crypto fortune—then David Rubio Gonzalez may know exactly where the money went. And with Maduro captured, that knowledge has never been more valuable.

The Gold-to-Crypto Pipeline

The $60 billion didn’t materialize from thin air. It was built through one of the most audacious financial operations in modern history: the systematic conversion of Venezuela’s gold reserves into untraceable cryptocurrency.

In 2018, as Venezuela’s economic crisis deepened and access to hard currency narrowed, the Maduro regime turned to gold. The country had been exporting gold for years, but now the operation scaled dramatically. Venezuela exported 73.2 tons of gold in 2018 alone—roughly $2.7 billion at the time.

Maduro placed the operation under the supervision of his close ally Tareck El Aissami, whom he appointed Minister of Industries and National Production. Alex Saab emerged as a central facilitator. The gold flowed to Turkey, where it was refined and sold. It flowed to the UAE, where it entered the global market. And in April 2020, tons of Venezuelan gold were flown to Iran on Mahan Air as part of a gold-for-gasoline swap.

Iran International reported that a Lloyd’s Insurance leak revealed the scheme was coordinated by the IRGC Quds Force and Hezbollah. Gold sold in Turkey and the Middle East generated proceeds that funded Hezbollah operations. Some nine tons of Venezuelan gold were exported in a single month, according to Bloomberg. In return, five Iranian oil tankers delivered an estimated 1.5 million barrels of gasoline to Venezuelan ports.

But gold is heavy. It’s traceable. It can be seized. The next step was converting it into something that couldn’t be touched.

Sources describe a systematic effort to convert gold proceeds into Bitcoin through OTC brokers in Turkey and the UAE—brokers who asked few questions and operated outside the traditional banking system. The Bitcoin was then moved through mixers, software that obscures the origin of cryptocurrency transactions, and into cold wallets: offline storage devices that exist beyond the reach of any government or exchange.

The timing was fortuitous. Venezuela began moving gold in earnest in 2018, when Bitcoin traded between $3,000 and $10,000. By the time the price peaked at $69,000 in November 2021, any holdings accumulated in those early years had multiplied by a factor of seven to twenty. If the regime converted even $3 billion in gold proceeds to Bitcoin at an average price of $5,000, those holdings would be worth $40 billion today.

PDVSA headquarters. By December 2025, Venezuela was collecting 80% of its oil revenue in USDT.

The crypto infrastructure didn’t stop with gold. Venezuela’s own PDVSA-Cripto corruption scandal revealed that Saab’s partner Álvaro Pulido—David’s father—used Tether-based settlement systems to divert billions in oil-sale proceeds. Between 2020 and 2022, PDVSA increasingly required intermediaries to settle oil cargos in Tether, routing payments through OTC brokers and private digital wallets.

The scandal revealed ships loaded with more than $20 billion worth of oil departing Venezuelan ports without payment ever reaching PDVSA. By December 2025, Venezuela was collecting 80% of its oil revenue in USDT. Tether has frozen 41 wallets containing $119 million linked to Venezuela—but that represents only what authorities have been able to trace.

The Architect

To understand how this system was built, you have to understand the man who built it.

Alex Saab was born in Barranquilla, Colombia, in 1971. He spent the 1990s running modest textile businesses. His career changed when he partnered with Álvaro Pulido, who was involved in drug trafficking and invited Saab to do business in Venezuela. Colombian left-wing senator Piedad Córdoba—who died in January 2024—introduced Saab to Maduro.

The contracts that followed were staggering in their brazenness. In 2011, Saab agreed to supply parts for 25,000 prefabricated houses under “Gran Mision Vivienda Venezuela.” The contract paid up to four times the actual cost. His company received $159 million to import housing kits but delivered only $3 million worth of products.

In 2016, when the regime launched the CLAP program to distribute subsidized food to families in need, Saab and Pulido built a network to exploit it. They sourced low-quality food from foreign suppliers, assembled the boxes abroad, and shipped them to Venezuela at inflated prices. To move funds and conceal the scheme, they used shell companies in Hong Kong, the UAE, and Turkey. The U.S. Treasury designated these networks in July 2019, calling them a “corruption network stealing from Venezuela’s food program.”

Alex Saab’s network spans shell companies, government officials, and international intermediaries across multiple continents.

Zair Mundaray, a former Venezuelan prosecutor who investigated Saab, told Whale Hunting that Saab slipped into Maduro’s inner circle precisely because he had no loyalties outside it. Unlike other power brokers in Caracas, Saab was not tied to any traditional political families or factions.

“Saab fits the profile of someone with no links to Venezuela’s traditional castes or power groups, whose only real connection is to the presidential family,” Mundaray said. “In Venezuela, power operates much more like a criminal cartel than an institutional structure. That creates a climate of mutual distrust and internal power struggles.”

Saab’s goal was simple: to make money, “and he found the perfect platform in a president who is himself a criminal.”

But Saab became more than a contractor. He became the guarantor of Maduro’s fortune.

“As the public and private spheres ultimately merge, there’s no distinction,” Mundaray said. “Saab is the guarantor of Maduro’s fortune — money dispersed across multiple countries and stored in different convertible assets that ensure him a life of luxury for generations, without ever lifting a finger.”

In April 2018, Maduro made it official, appointing Saab as Special Envoy with “broad powers to carry out actions on behalf of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela.” He was no longer a contractor. He was a diplomat.

The Double Agent