Authored by Gail Tverberg via Our Finite World,

Today’s economy is like that of the late 1920s…

Today, there is great wage and wealth disparity, just as there was in the late 1920s. Recent energy consumption growth has been low, just as it was in the 1920s. A significant difference today is that the debt level of the US government is already at an extraordinarily high level. Adding more debt now is fraught with peril.

Figure 1. US Gross Federal Debt as a percentage of GDP, based on data of the Federal Reserve of St. Louis. Unsafe level above 90% of GDP is based on an analysis by Reinhart and Rogoff.

Where could the economy go from here? In this post, I look at some historical relationships to understand better where the economy has been and where it could be headed. While debt levels and interest rates are important to the economy, a growing supply of suitable inexpensive energy products is just as important.

At the end, I speculate a little regarding where the US, Canada, and Europe could be headed. Division of current economies into parts could be ahead. While the problems of the late 1920s eventually led to World War II, it may be possible for the parts that are better supplied with energy resources to avoid getting into another major war, at least for a while.

[1] Government regulators have been using interest rates and debt availability for a very long time to try to regulate how the economy operates.

I have chosen to analyze US data because the US is the world’s largest economy. The US is also the holder of the world’s “reserve currency,” allowing demand for the US dollar (really US debt) to stay high because of its demand for use in international trade.

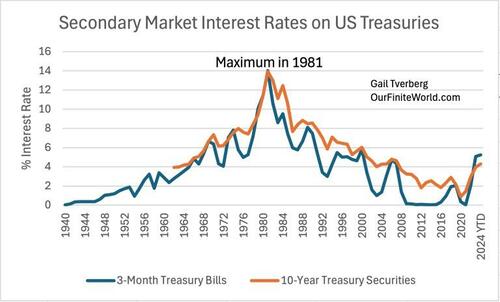

Figure 2. Secondary market interest rates on 3-month US Treasury Bills and 10-year US Treasury Securities, based on data accessed through the Federal Reserve of St. Louis. Amounts for 1940 through 2023 are annual averages. Amount for 2024 YTD is average of January to July 2024 amounts.

Comparing Figure 1 and Figure 2, it is clear that there is a close relationship between the charts. In particular, the highest interest rate in 1981 on Figure 2 corresponds to the lowest ratio of US government debt to GDP on Figure 1.

Up until 1981, the changes in interest rates were either imposed by market forces (“You can’t borrow that much without paying a higher rate”) or else as part of an attempt by the US Federal Reserve to slow an economy that was growing too fast for the available labor supply. After 1981, the same market dynamics no doubt took place, but the overall attempt at intervention by the US Federal Reserve seems to have been in the direction of speeding up an economy that wasn’t growing as fast as desired.

In Figure 2, the 3-month interest rates correspond fairly closely to government target interest rates. The 10-year interest rates tend to move on their own, perhaps somewhat influenced by Quantitative Easing (QE), in which the US government buys back some of its own debt to try to hold down longer-term interest rates. These longer-term interest rates influence US long-term mortgage interest rates.

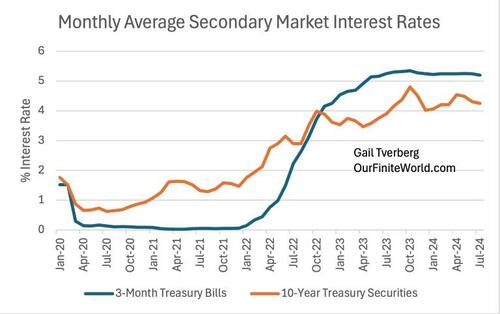

Recent monthly data show that 10-year interest rates started rising very quickly after reaching a minimum following the Covid response in early 2020. The lowest 10-year average rates took place in July 2020, and rates started moving up in August 2020.

Figure 3. Monthly average secondary market interest rates on 3-month US Treasury Bills and 10-year US Treasury Securities, based on data accessed through the Federal Reserve of St. Louis.

This suggests to me that market forces play a significant role in 10-year interest rates. As soon as people started borrowing money to remodel or to move to a new suburban location, 10-year interest rates, and likely the related mortgage rates, started to drift upward again. If this observation is correct, the Federal Reserve has some control over interest rates, but it cannot adjust the 10-year interest rates underlying mortgages and other long-term debt by as much as it might like.

The apparent inability of the Federal Reserve to adjust longer-term interest rates to as low a level as it would like is concerning because the US government debt level is very high now (Figure 1). Being forced to pay 4% (or more) on long-term debt that rolls over could create a huge cash flow issue for the US government. More debt could be required simply to pay interest on existing debt!

[2] An analysis of actual growth in US GDP over time shows how successful the changing strategies in Figures 1 and 2 have been.

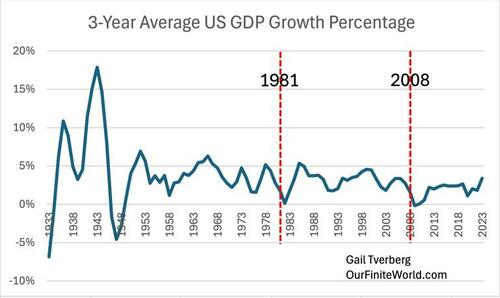

Figure 4. Three-year average US inflation-adjusted GDP growth rates based on data of the US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

In the 1930s, the US and much of the rest of the world were in the Great Depression. Interest rates were close to 0% (not shown on Figure 2, but available from the same data). Various versions of the New Deal under President Roosevelt were started in 1933 to 1945. Social Security was added in 1935. Figure 4 shows that these programs temporarily increased GDP, but they did not entirely solve the problem that had been caused by defaulting debt and failing banks.

Entering World War II was a huge success for increasing US GDP (Figure 4). Many more women were added to the workforce, making munitions and taking over jobs that men had held before they were drafted into the army.

After the war was over, the total number of jobs available dropped greatly. Somehow, private sector growth needed to be ramped, using debt of some kind, to provide jobs for the returning soldiers and others left without work. An abundant supply of fossil fuels was available, if debt-based demand could be put into place to pull the economy along. Programs were put into place to get factories running again making goods for the civilian economy.

Upgrading the electrical grid, expanding pipeline infrastructure, and initiating work on an interstate highway system in 1956 led to the creation of additional jobs and an increased demand for energy.

From 1950 to 2023, the US economy experienced a gradual decline in average growth rate despite the implementation of debt-based stimulus measures. Economic growth relies on the production of physical goods and services, which, according to the laws of physics, necessitates appropriate energy supplies.

The growth rate of world energy supply has been decreasing over time, as the extraction of the easiest and cheapest fossil fuels is prioritized. Comparing Figures 5 and 6, it is evident that US GDP growth aligned with global energy supply growth in the periods of 1950-1970 and 1971-1980. However, in the period of 1981-2007, US GDP growth surpassed world energy consumption growth due to a shift towards a service economy and increased outsourcing of industrial production.

The recent low growth in energy supplies has created economic challenges that have been masked by increased debt. The world economy today mirrors that of the 1920s, characterized by rising debt levels, wage disparities, and innovation. Low energy growth periods, such as the years 2008-2023, lead to slower economic growth, low interest rates, and widening wealth gaps. Physicist Francois Roddier’s theory suggests that low energy supply results in diverging income levels, with the majority of wealth existing as future promises dependent on sufficient energy availability. The population grew by 1.1% per year in both the 1920s and the latest period (2008-2023). However, net energy consumption per capita growth was slightly negative (-0.1%) in the 1920s and only a very small positive percentage (0.4%) in the 2008-2023 period. Per capita consumption had been growing much more quickly between 1950 and 1980.

The economy becomes very fragile when the growth of energy supply is low compared to the growth of the world’s population. This can lead to problems such as large wage disparities, excessive influence of very rich individuals, and a drive for profits that can overshadow the well-being of citizens.

As the world transitions from a growth mode to a mode of shrinkage, concerns arise about the declining growth in the consumption of fossil fuel energy supplies. The amount of growth in energy supply determines the production of physical goods and services. Repaying debt with interest becomes more difficult in a shrinking economy, as investments struggle to repay loans requiring interest.

Despite government-funded investments in green energy, world CO2 emissions continue to rise. History since 1920 suggests that the future may not turn out well, with potential collapses in stock markets, drops in asset prices, debt defaults, and failing financial institutions. These challenges can lead to a decline in commodity prices and worsen the financial situation for farmers.

[7] Potential Consequences of Economic Challenges

As a response to economic challenges, governments may implement various strategies to mitigate the negative impacts. Some of these strategies include:

(e) Increase in Debt-Based Money: In an attempt to raise prices, a government may choose to issue more debt-based money. However, this approach may lead to hyperinflation if not supported by local production capabilities.

(f) Persecution of Wealthier Individuals: During times of scarcity, there is a tendency to blame wealthier individuals for societal problems. This has historically led to persecution, as seen in events like the Holocaust where Jews were targeted.

(g) Resort to War: War presents an opportunity to acquire resources from other regions, thereby boosting GDP and providing employment opportunities. However, it is not a sustainable solution to resource scarcity.

[8] Political Approaches to Address Challenges

While no political approach can fully avert the consequences discussed above, certain strategies can help countries navigate these challenges:

– Developing self-sufficient supply chains based on domestic resources can provide some insulation against economic shocks, although few advanced countries currently meet this criterion.

– Implementing tariffs on imports, as advocated by some leaders, can promote economic independence but may also lead to trade conflicts and shortages.

– Providing financial support to the poor may increase government debt and devalue currencies, impacting global trade and availability of imported goods.

– Embracing renewable energy sources like wind and solar power can contribute to long-term sustainability, but excessive debt financing of these initiatives may have adverse effects.

[9] Future Scenarios for US, Canada, and Europe

The political landscape in the US, Canada, and Europe may diverge based on differing approaches to economic challenges:

– Regions with abundant resources, such as the central US and parts of Canada, may lean towards self-reliance strategies like tariffs and local production.

– Highly populated coastal areas may opt for debt-based policies to sustain their economies, leading to potential divisions within countries.

– A scenario could unfold where the US splits into two sections, with one focusing on self-sufficiency and the other on debt-driven policies, potentially aligning with Europe in conflicts.

Ultimately, the choices made by political leaders will shape the future trajectory of these regions, impacting trade, security, and economic stability.

sentence: Can you please rewrite the sentence?